Bouffe Front presentation at SFEIR: How to make fast web frontends

I presented my article How to make fast web frontends at the SFEIR Bouffe Front event, in French.

I put here a translated version of the presentation. You can also check out the slides and the script of the talk, in french, on the page:Présentation Bouffe Front à SFEIR: Comment faire des frontends web performants

Introduction

Hello everyone. Today, I am going to present some diagrams from my article: “How to Create High-Performance Web Frontends”.

The article has three chapters:

- The first chapter aims to raise awareness that the web relies on a physical infrastructure.

- The second chapter covers optimizations that reduce the use of physical resources by web pages.

- And the third chapter addresses optimizations that improve performance by reducing user wait times.

Similarly, this presentation is divided into three parts:

- The first part addresses the environmental footprint of the web.

- In the second and third parts, I will present diagrams explaining some optimizations.

I have marked certain topics as “à la carte.” These are subjects for which I have diagrams but are not included in this presentation. We can look at them together afterward, if you’d like.

The web is build on a physical infrastructure.

In the background, you can see images of a mine, a data center, a waste disposal site full of phones, and a field covered with solar panels.

A common measure of the environmental impact of economic sectors is the amount of greenhouse gases emitted.

In terms of this type of pollution, the internet is comparable to aviation.

In this diagram, I break down the emissions attributed to the internet.

- The blue represents emissions from hardware manufacturing: user devices, data centers, and the network.

- The yellow shows the emissions generated during the use of this hardware.

We can see that the footprint of user devices is greater than that of data centers and the network combined. This is probably due to the huge number of devices in use.

We also see that about half of the emissions attributed to user devices come from their manufacturing, while the other half comes from their use. In contrast, data centers and the network emit 82% of greenhouse gases during use, compared to 18% during manufacturing. One possible explanation for this difference with user devices is that data centers and the network belong to economic players who aim to maximize the long-term profitability of their hardware.

The environmental impact of the web is not limited to its carbon footprint. It takes an industry to produce and power the web, and this industry competes for resources with other inhabitants of the planet, hence this diagram.

In this second version of the diagram, I show what happens when we rely on more hardware, and more powerful hardware, to improve web performance. We get a web that mobilizes a larger industry, and thus leaves less space for nature.

To conclude this first part of the presentation, I invite you to join the “Numérique Responsable” group at SFEIR.

In fact, it was through a quiz organized by this group that I learned that user devices and thus frontends represent a significant part of the web’s environmental footprint.

Part 2: How to Optimize Web Performance by Using Less Resources

Often, on the web, we find websites that are heavy not because of their content, but because they integrate unnecessary elements.

Therefore, before looking for technical solutions, the first optimization is to include only what is really necessary.

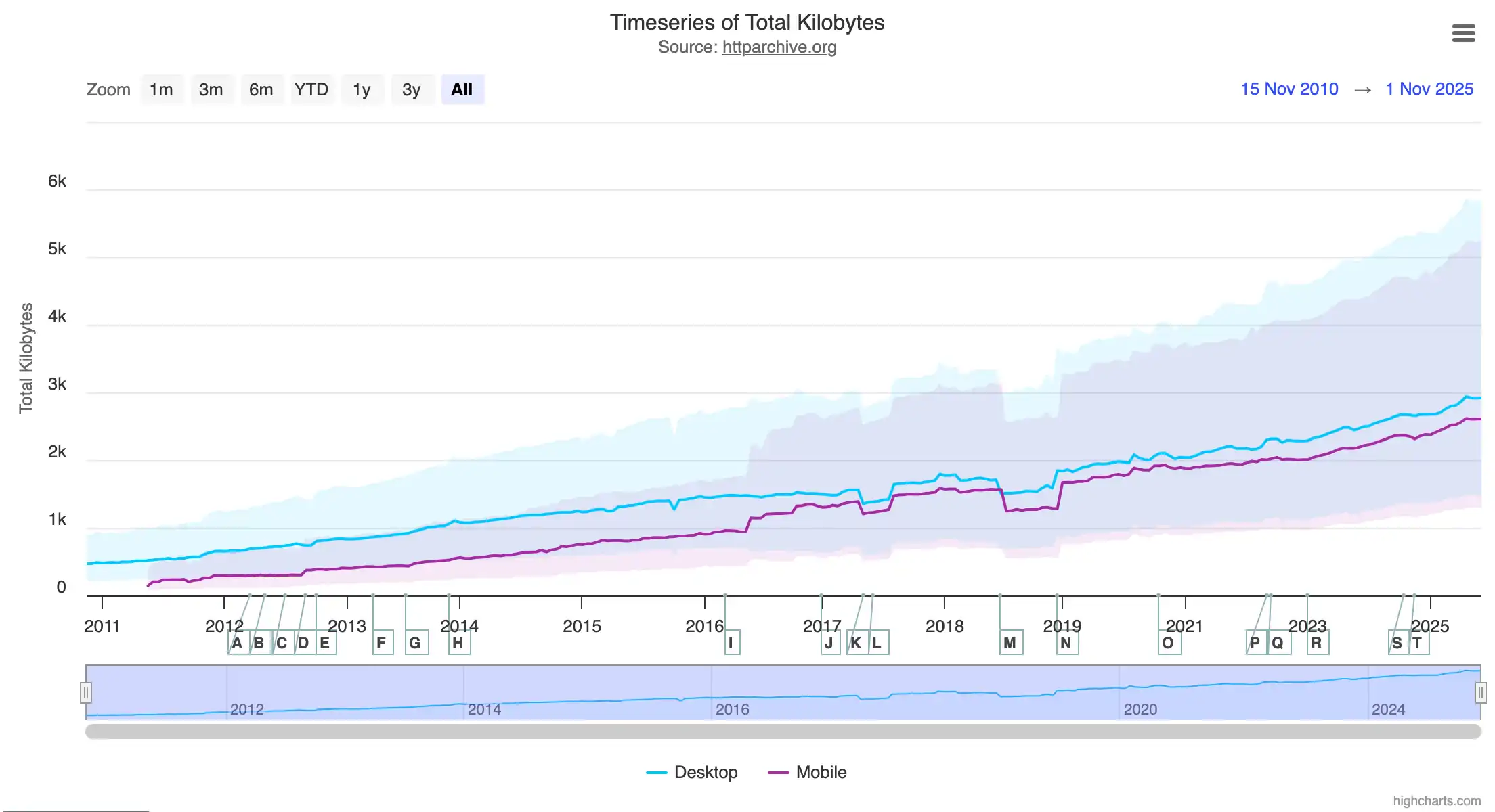

This diagram, taken from the HTTP Archive website, shows that the median size of a web page was 0.47 MB in 2010. Today, the median page weighs 2.9 MB, which is six times more.

For comparison, my article, which is full of diagrams and which takes about 3 hours or more to read, is only 0.18 MB.

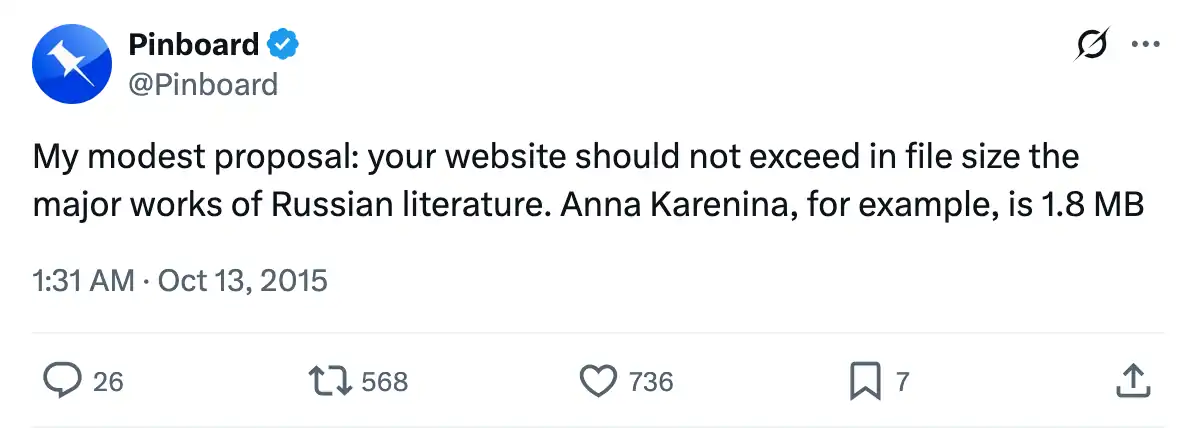

For another point of comparison, I like to quote this tweet from Pinboard: “Your website should not exceed in file size the major works of Russian literature.” He mentions a novel that weighs 1.8 MB.

I took this quote from the 2015 presentation “The Website Obesity Crisis,” which is both interesting and funny.

Now, let’s move on to the technical approaches for performance optimization.

Caching

A cache is a memory that temporarily stores a copy of data to reduce access time for subsequent requests.

This example illustrates how caching helps save server and network resources.

The example involves four entities: client 1 and its cache, client 2 and its cache, a shared cache for all clients, and a server.

When client 1 requests our page, its request reaches the server, which generates a response. This response is stored in the shared cache.

When client 2 requests the same page, the shared cache responds directly, without involving the server, thereby reducing the server load.

The server’s response is also stored in each client’s cache.

When clients request the page for the second time, it is served directly from their local cache, reducing the network load.

Now, what if we have a page with a dynamic part that should not be cached.

Should we abandon caching for the entire page? Not necessarily.

We can serve the static part separately from the dynamic part. This way, the static part benefits fully from caching, and we manage to load an up-to-date version of the dynamic section.

This is illustrated in this example with three entities: the client and its cache, the shared cache, and the server.

The client makes a GET request to retrieve the page. Then, it makes a second request to retrieve the dynamic section.

The static part of the page is returned directly from the shared cache. As for the request to retrieve the dynamic section, it reaches the server, which responds with an HTTP header Cache-Control: no-store to indicate to the cache not to store it.

When the same client loads the page again, the static part is fetched directly from the local cache, and the dynamic section is fetched from the server.

In the article, you’ll find more explanations and detailed diagrams explaining how HTTP caching works. If the titles on this slide interest you, or if you’re unsure about what the HTTP headers on the right do (for example, what ETag or If-None-Match are), I invite you to consult the article.

Before finishing the section on caching, I would like to mention CDNs (Content Delivery Networks), which help improve performance when a website’s clients are spread across the globe.

Imagine a server located in France and two clients: one in Quebec and the other in South Africa.

The physical distance between the clients and the server increases the loading times of requests.

This can be explained by the fact that data travels at a speed slower than that of light, which itself takes about 130 milliseconds to circle the Earth.

To solve this problem, CDNs (Content Delivery Networks) offer a decentralized cache network with Points of Presence (PoPs) spread across the world.

With a CDN, when a client requests data available in the cache, it receives the response from the closest PoP, drastically reducing the loading time.

When a request cannot be fulfilled by the cache, it must be sent to the server, generating a higher loading time (but this now concerns a reduced number of requests, represented here by a thin line).

Reducing Client-Side Code Size

Now, let’s look at optimizations that reduce the load on the network and user devices by reducing the size of client-side code.

First, there are optimizations made by the bundler or the compiler. If you’re using a framework, it handles this automatically for you. However, it’s important to understand these optimizations and choose libraries that do not hinder them. I discuss this in the article, but I don’t have a diagram to show you about it.

The second point is using lightweight libraries.

Here, as an example, I show two implementations of the same application, each containing 50 KB of application code.

The left implementation uses very popular but relatively heavy libraries (React, Next, MUI Date Picker, and reCAPTCHA). The bundle size for this implementation is 508 KB.

The right implementation is made with lighter libraries and weighs less than 100 KB, which is less than one-fifth of the first.

A third approach to reducing the size of client-side code is to keep part of the code on the server.

When the client needs to use this code, it must make a call to the server. Inputs and outputs will then transit over the network.

This involves a trade-off between sending the code and sending the inputs/outputs of the code.

One type of code that can benefit from this optimization is the code responsible for rendering (i.e., generating the HTML from the data).

Frameworks provide us with several possible approaches: CSR, SSR, and Hydration.

Based on the release dates of frameworks that popularized CSR, SSR, and hydration, or even their general popularity in the frontend community, one might think that SSR is inferior to CSR, which is in turn inferior to hydration.

To understand why this is not the case, let’s first recall how these approaches work, using sequence diagrams.

Let’s start with SSR (Server-Side Rendering).

The user navigates to the page. The client makes calls to the Frontend Server, which in turn calls the backend. The backend responds with the raw data. The Frontend Server returns the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files. Finally, the client displays the page on the screen for the user, then makes it interactive once the script is loaded.

Before highlighting the advantages and disadvantages of SSR, let’s first compare it with CSR (Client-Side Rendering).

The user navigates to the page. The client loads an empty page from the Frontend Server. It then downloads the page script. This script then downloads the data from the backend. Finally, the client generates the HTML from the data and displays the page on the screen.

In fact, CSR rendering has several problems.

- First, the server sends an empty page, which can be interpreted as a “blank page” by search engines that do not execute JavaScript. This is not ideal for SEO (Search Engine Optimization).

- Then, the data is downloaded later than with SSR: we first download the script before downloading the data.

- The page itself is displayed later.

- Finally, the client has to download both the rendering code and the interactivity code.

The positive side of CSR is that the code is declarative and easy to write and maintain.

Now, let’s revisit the sequence diagram for SSR:

- We download the data early from the backend.

- We display the page to the client early.

- We only download the code necessary for interactivity because the HTML rendering is done server-side.

The downside is that the code responsible for managing interactivity is imperative, making it potentially more difficult to write and maintain.

This is why hybrid rendering approaches, combining SSR and CSR, have been developed. The most common of these approaches is hydration.

The same declarative JavaScript code can run on both the server and the client. When the page loads on the server, the Frontend Server generates the HTML. On the client side, the framework attaches event handlers to this HTML to make it interactive.

Thus, with hydration, like with pure SSR:

- We load the data early,

- We don’t send an empty page,

- And we display the page quickly on the screen.

So we combine the benefits of CSR and SSR: declarative code and good performance.

But that’s not the whole story.

Let’s compare the data sent to clients with SSR, CSR, and hydration.

We will examine what needs to be sent in terms of:

- Client-side JavaScript code

- Raw data (e.g., in JSON format)

- HTML code

I use as an example a page with two HTML templates. Template 1 is instantiated once, and Template 2 is instantiated three times, each with different data.

With SSR, we send the templates and the data in HTML form. We can see that Template 2 is repeated three times in the HTML.

We also send the code necessary to make Templates 1 and 2 interactive.

With CSR, we send almost nothing in the HTML. We send the raw data to the client. And we send the JavaScript code for rendering and interactivity for both templates.

Notice that Template 2 is not sent multiple times to the client, as with SSR.

With hydration, we send the code for both templates and their interactivity, as with CSR. Additionally, we need to send the framework code that implements hydration. We also send the data in raw form, as with CSR. We send the templates and data a second time in the HTML.

We also notice that Template 2 is repeated three times, just like with SSR. And as a bonus, we send metadata to support hydration.

We can see that hydration should not be chosen blindly. Sometimes, SSR or CSR provide better performance.

I discuss partial hydration in the article, which attempts to address these issues. Additionally, hydration is not the only way to hybridize SSR and CSR.

Part 3: Smart Scheduling

Let’s now move to part 3 of the presentation: how to optimize performance, not necessarily by reducing resource usage, but by reducing user wait times through smart scheduling.

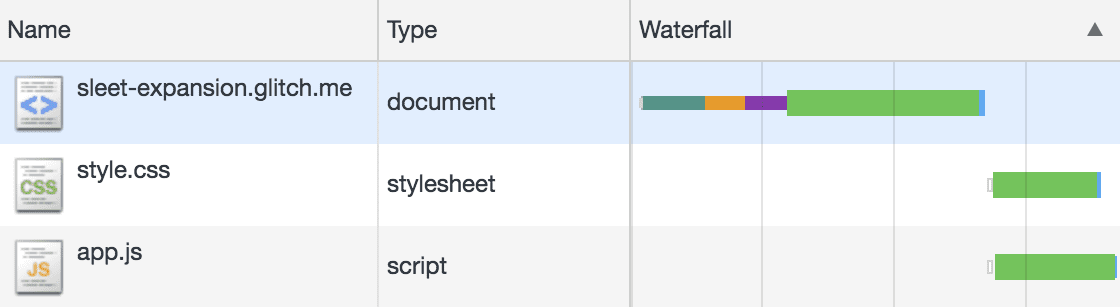

In this section, we’ll see a lot of Gantt charts like this one.

On the web, these diagrams are called “waterfall diagrams”, and they can be visualized in the “Network” tab of your browser’s developer tools.

That said, the diagrams in my article are generated by simulation. They not only include client-side tasks but also server-side ones. And thanks to the simulation code, I can control the network parameters in a reproducible way.

Do Not Block the Main Thread

The first optimization, or rather, mistake to avoid, is blocking the main thread of the web page.

In this example, the user clicks twice: once at time 0, and again at 500 milliseconds.

After the first click, the browser executes the code “handle click #1.” This code finishes quickly, but it triggers a long-running task that takes a lot of time to complete.

When the user clicks the second time, the main thread is occupied with that long task. Only after this task finishes can the browser process the second click.

When the “handle click 2” code finishes, the browser recalculates the layout of the page and displays the result at 1000 milliseconds.

One way to avoid this issue is by breaking the long task into several smaller tasks that periodically release the main thread, allowing the browser to handle user-generated events.

In this example, when the user clicks a second time, the main thread is blocked, but not for long.

After less than 100 milliseconds, the browser executes the “handle click 2” code, recalculates the layout, and displays the result at 720 milliseconds.

Another way to approach this problem is to run the long task outside the main thread. This is possible thanks to the Web Workers API.

So, when the user clicks a second time, the browser directly handles this event. The page is then displayed at 650 milliseconds.

Streaming

Now let’s look at more interesting optimizations that involve the client, server, and network: starting with streaming.

Here’s the Gantt chart for loading a web page containing a style.css file and a script.js file.

The goal is for the browser to be able to calculate the layout (the blue task) as early as possible so that it can display the page on the screen.

Let’s zoom in on this part of the chart to explain the principle.

In this diagram, I display both client-side and server-side tasks. For the page.html file, I show two lines: one for loading the page on the client side and another for generating the page on the server side.

The client sends a request to download the page. Before the request reaches the server, we first need to wait for the first byte of the request to travel physically between the client and the server (this is the network latency). Then, we need to wait for the transmission time of the HTTP request content.

Once the server receives the request, it generates the head and body of the page. Then, it sends them to the client.

After a network latency delay, the client receives the head content of the page, followed by the body content.

Now, let’s see what happens with streaming, which is simply sending the data progressively.

The client sends a request to download the page. The server generates the head of the page and sends it to the client. In parallel, the server generates the body of the page. Once ready, it transmits it to the client.

Let’s go back to our diagram for loading a page without streaming.

The client requests the page.html file. The server takes a few milliseconds to generate the head of the page. Then, it takes 250 milliseconds to generate the body. Once the head and body are ready, the server sends the response to the client.

As soon as the client receives the head, and without waiting for the body to arrive, it can begin downloading the style and script files. It then sends two requests to the server.

The server quickly responds to these static file requests.

Once the style and script files are downloaded and interpreted, the browser calculates the layout of the page and displays it on the screen at time t=1000 ms.

Notice that the client cannot begin downloading the style and script files until the body of the page has been generated on the server side.

Now let’s see what happens when we use streaming.

The client sends a request for the HTML page. The server generates the head, then in parallel, it begins generating the body and sends the head to the client. As soon as the client has downloaded the head, it sends requests to download the style and script. The server responds to these requests and continues generating the body. Once the body is generated and transmitted to the client, and once the client has finished interpreting the style and script, it calculates the layout and displays the page at time T = 785 ms, more than 200 milliseconds earlier than without streaming.

Streaming allowed the client to begin downloading the style and script files soon after the head of the page was generated on the server side. It downloads them in parallel with the generation of the body on the server.

Let’s now examine a more advanced application of streaming: “out-of-order streaming,” implemented by MarkoJS in 2014, and more recently by popular frameworks like Next.js at late 2022.

In this example, we have a page that loads a style.css file and a script.js file. On the server side, to generate this page, the server uses three threads to generate three sections of the page in parallel.

This implementation uses “in-order streaming,” meaning that section 1 must be delivered to the client before section 2, and so on.

The client sends a request for the page.html file. The server generates the head, then in parallel, sends the head to the client and begins generating the three sections of the page.

The client downloads and interprets the style and script.js files. You can see that thread 2 has finished generating section 2. But since the page is streamed in order, and section 1 is not yet ready, section 2 must wait.

As a result, the client shows an empty page skeleton on the screen. Once section 1 is generated, the server streams all three sections to the client, and the client displays them as they arrive.

Now let’s see how the same page loads when we use “out-of-order streaming.”

The client makes the request for page.html. The server generates the head. In parallel, it streams the head to the client and begins generating the three sections of the page. The client downloads and interprets the style and script.js files. Once section 2 is generated on the server, it is streamed to the client. As a result, the browser already has section 2 and can display it on the screen. This happens at 770 ms, 400 milliseconds earlier than in the previous example. Then, as the other sections are generated and streamed to the client, they are displayed by the client.

Preloading

Let’s now move to the next optimization: “preloading,” which allows us to eliminate even more unnecessary wait times.

For preloading, I created this example with an HTML page that loads a style.css file, which in turn imports another file style-dependency.css.

This diagram shows how the page loads without using preloading. The client requests the HTML page. One difference from previous diagrams is that for this example, the server takes 250 milliseconds to determine the status code of the page (for example, whether it should respond with a 200 OK or 404 Not Found).

Once the status code is determined, the server generates the head of the page and sends the status code to the client in parallel.

Once the head is generated and served to the client, the client sees the <style> tag and starts downloading the style.css file.

Once style.css is downloaded, the client sees the @import statement and starts downloading the style-dependency.css file.

After both files are downloaded and interpreted, the client calculates the layout and displays the page on the screen.

Thus, we observe two dependencies:

- The

style.cssfile cannot be downloaded until the head is generated and received on the client side. - The

style-dependency.cssfile cannot be downloaded untilstyle.cssis received on the client side.

Here’s the same page, but with a <link rel="preload"> tag to preload the style-dependency.css file. A <link rel="preload"> tag allows you to load a resource without inserting it directly into the page. This way, when the resource is actually needed, it will already be loaded or in the process of being loaded.

Here’s the diagram for loading the page with this preload tag. We won’t go into full detail, but the key point is that as soon as the client receives the head of the page, it can download both the style.css and style-dependency.css files.

In fact, we can do even better: we can preload using HTTP headers. These headers look like this. They can be sent even before the head of the page is generated.

Furthermore, for almost two years now, all modern browsers (except Safari) support sending preload headers, even before the status code of the page is determined, thanks to a special status code: the 103 Early Hints.

With this optimization, when the server receives the request, it instantly responds with a status code of 103 Early Hints and preload headers, allowing the client to start downloading the style.css and style-dependency.css files even before the status code of the page is determined.

For a second example of preloading, let’s look at how to speed up the initial load of a Single Page Application (SPA) that uses CSR.

This page loads a style file, a script, and a data.json file. The server quickly responds with an empty page because we are doing client-side rendering (CSR).

Without preloading, the client receives the page and starts loading the style and script. When the script runs, it makes a request to download the data.json file, and only after the client has received this file can it display the content of the page.

Now, let’s look at the same example, but with the use of a <link rel="preload"> tag to preload the data.json file.

When the client receives the HTML page, it immediately starts downloading all three resources for the page. When the script runs, it tries to load data.json, but it’s already in the cache. As a result, no round trip to the server is needed, and the page content is displayed quickly.

I refer you to the article for more diagrams, examples, and preloading scenarios.

Conclusion

To conclude:

- In the first part of the presentation, we saw how the Web is a physical system.

- In the second part, we discussed optimizations that reduce resource usage.

- In the third part, we looked at optimizations aimed at eliminating unnecessary wait times.

There’s still much more to explore in the article, which includes 117 external links and a total of 55 diagrams.

Thank you for your attention.